A HISTORY OF THE PENINSULA PROPERTY

While the Peninsula as a community and championship golf course was originally conceived and developed during the last decades of the 20th century, the property itself has a unique and colorful past going back over one thousand years. Defined on the north by the bountiful waters of Bon Secour Bay, and on the south by the quiet Little Lagoon, the plethora of prehistoric sites that surround the neighborhood are a testament to it’s enduring allure. Ecologically, the property consists of sandy shorelines, tidal salt marshes, swamps, mixed hardwood and pine forests, and lastly an ancient dune system, some of which soar up to 20 feet above sea level. Formerly part of the French, Spanish and British empires, the acreage has also had a hand in some of the United States’ earliest pivotal conflicts. There’s little doubt that when Kenny McLean and David Head first set out to create the Peninsula, not only did they have an eye for prime real estate, it’s clear they had a keen sense of history.

EARLY HISTORY

Emanating from Bear Point in Orange Beach and varying from a half-mile to a full mile in width, a majority of the Peninsula development is situated along an elevated East-West ridge that extends almost entirely to Mobile Point. Considering that there over two dozen primitive Native American sites that have been recorded within a mile of the community, there’s little doubt that the significance of this naturally dry path through the wetlands was not lost on the ancient cultures that thrived in the area. In addition to the nearby mounds, village sites, numerous fishing camps and the rare artificial canal, the recent discovery of a probable ancient portage road is the archaeological feature most intimately associated with the Peninsula. This once well-worn trail was the quickest and most efficient passageway for the aboriginal inhabitants transporting dugout canoes between the bay and their large fishing campsite on the lagoon. While written accounts of these cultures don’t appear until the 1500s with the arrival of the first Spanish expeditions, the vestiges of the remote past that encompass the Peninsula community continue to be a rich source of fascination and knowledge that will inform our understanding of history for generations to come.

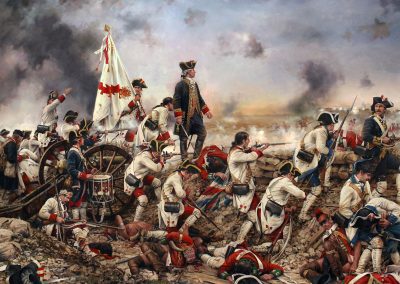

Subsequent to the initial influx of daring, international explorers seeking new lands and the promise of fortune, the ensuing centuries would also mark the beginning of a global power struggle linked to the Peninsula property that would linger until 1819 when the Florida Territory was purchased by the United States. First claimed by both France and Spain beginning in the early 1700s, the future residential tracts would formally become part of British West Florida after the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763. However, following the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, Spain, implored by George Washington himself, would soon seize the land. In March of 1781, after sailing from Mobile and camping near Oyster Bay, Spanish troops and artillery engineers marched through what very well could be the Haven neighborhood, en route to support Bernardo de Galvéz’s fateful naval attack and siege of Pensacola. The eventual surrender of the city would lead to the creation of Spanish West Florida and generate the first land grants from the King directly associated with the neighborhood. However, the property brawl was far from over and as the United States continued to grow, the approaching War of 1812 would open and close the final chapter on ownership of the region.

THE 1800s

In mid April of 1813, the United States military siezed Fort Charlotte in Mobile and took control of the country all the way to the Perdido River. Forcing the Spanish to retreat to Pensacola, this occupation of Mobile brought the future golf club acreage into the US controlled Mississippi Territory. The infantry would also fortify Mobile Point and modern-day Lillian which were connected by a series of crude roads, one of which ran right through the Peninsula. The following September, hoping to contain the steady US expansion, the British Royal Navy, who had secretly re-entered Pensacola while preparing to invade New Orleans, launched a failed attack on the Fort Bowyer at Mobile Point. After the disastrous assault, a special force of 100 Royal Marines and 300 allied Creek warriors that had been deployed as ground support prior to the battle, hurriedly made their retreat east to rendezvous with the rear guard at Bon Secour.

As they kept to the road that ran approximately the course of Lagoon Dr. and Peninsula Blvd., the detachment would later narrowly avoid the swift pursuit of the 3rd US Infantry, escaping across Perdido Bay in the dead of night and returning safely to Spanish held Pensacola. This unsuccessful Naval operation, along with the British defeat at New Orleans shortly afterwards, effectively signaled the termination of the major international contest over control of the property that now comprises the community.

For roughly the next 100 years, the Peninsula acreage would remain part of what one early Scottish cartographer noted as being “nearly an uninhabited desert”. Though it was a region commonly referred to only as the “country between Mobile and Pensacola”, every so often there were some extraordinary passersby on the narrow path that previously ran through the interior of the future parcels. Initially, the implementation of the Indian Removal Act in 1830 would send scores of Native Americans fleeing down the old road towards Florida from the deplorable conditions at Fort Morgan, where they were quartered while awaiting passage by ship to their new lands west of the Mississippi River. Later, during most of the American Civil War, swarms of Confederate cavalry scouts regularly used the same crooked course as a vital communications corridor to keep tabs on the Union blockade fleet. In late 1864 however, those rebel patrols would dissolve into thousands of Federal troops, engineering corps, artillery units and supply wagon trains marching east from the captured fort, bound for the last major battle of the War Between the States across the bay from Mobile at Fort Blakeley. Eventually, the fragile postwar years witnessed a return to the growth that had been halted by the great conflict. As the old trail continued to be the main east and west route connecting Mobile Point to the mainland, it facilitated the arrival of numerous pioneering homesteaders and supported the expansion of the local logging, turpentine and fishing industries. Lastly and perhaps most critical, the road expedited the establishment of several nearby settlements that would mature and consolidate into the prosperous municipality that we know today.

MODERN ERA

Laying the framework for what would become a tourist destination welcoming more than 6 million visitors annually, the Depression-era Works Progress Administration projects delivered not only the Intracoastal Canal, the 4,500 acre Gulf State Park and Foley-Gulf Highway, it also brought the brand new 21-mile paved road connecting the state park to Fort Morgan. When this parkway opened up in the late 1930s skirting practically the entire Alabama coastline, it marked the end of heavy traffic on the old trail through the future Peninsula but at the time, it was the only point between Apalachicola and Galveston where the Gulf of America could be reached by road without unusual difficulty. Most importantly however, this era carried with it Mr. George C. Meyer’s ambitious dream for Gulf Shores. A humanitarian and visionary, Mr. Meyer established the first homestead south of the Little Lagoon in 1921 and after many years of acquiring property and promoting development along Baldwin County’s coastline, he established the George C. Meyer Foundation which guaranteed his charitable philosophy and civic works in the community endured after his passing in the late 1950s. Having donated over a thousand acres for preservation and public use since it’s inception, the Meyer Foundation owned a majority of the property when in 1984, another local real estate visionary Mr. Wade Ward, designed the original idea for what would become the Peninsula. Although the 340 acre “Blue Heron Bay” development that included residential units, a golf course, tennis courts, and a clubhouse/conference center never got the chance to be fully realized, it set the stage for H/M Partners a decade later to pick up where Mr. Ward had left off.

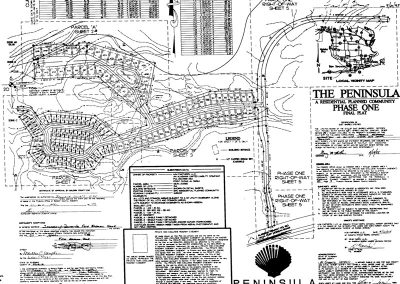

In October of 1994, after the runaway success of their Rock Creek development in Fairhope the year before, H/M Partners (Kenny McLean and David Head) signed the deeds for the 717 acres that would comprise the original Peninsula development. The following April, as all of the official documents were being finalized and entered into the Baldwin county records, Rock Creek was already selling Phase III lots. Despite the blistering pace of success in Fairhope, the Peninsula struggled to repeat the achievements of it’s predecessor and by August of 1999, units within the Racquet Club Condominiums and Phase I parcels, now known as The Lakes, were still readily available. Two months later however, after purchasing its first course at Rock Creek over the summer, the newly formed Honours Golf (Bob Barrett, Bob Julian and Rob Shults) based in Birmingham, acquired the Peninsula golf course producing a massive momentum shift. Seeing potential in the Gulf Shores enterprise, they would also purchase the remaining acreage under the Peninsula Land Investment Company and as roughly half of the development contained protected wetlands, it’s evident that the Honours team had preservation in mind as they moved forward with their new property.

Besides the Racquet Club and Links condos, there had been no significant changes to the original Peninsula layout prior to the Honours acquisition but by the end of 2002, 3 major expansion projects had been put into motion. The Preserve, Baywalk and Boulevard additions marked Honours commitment to not only excellence in golf course management, but their lasting investment in the communities that host those courses. Naturally, as the Peninsula began to attract more players and property owners following the establishment of these new phases, the resulting success would usher in another period of growth. Over the next 4 years, the Links Golf Villas, Retreat and Haven projects were introduced to the Master Plan and by 2007, Honours had not only created significant improvements to the development, they had nearly tripled the size of the property from the original deeds.

In July of 2023 Peninsula Golf and Racquet Club was purchased by Scratch Golf, a division of the United Company of Bristol, VA. Scratch Golf Company was originally formed for the sole purpose of providing superbly conditioned and professionally managed facilities for the golfing public’s enjoyment. This successful approach resulted in sustained growth as Scratch Golf continued to establish its presence in the golf industry.

The United Company was also growing, especially in the hospitality and leisure sector of Scratch Golf. Their offerings now included public, private and semi-private golf courses, as well as RV resorts and a vintage car company. The United Company recognized this transition and opted to rebrand Scratch Golf with a name which would encompass the entire sector. In 2024 Thistle Hill Properties was introduced, and Peninsula joined this collection of premier destinations which provide the world’s best guest experiences.

Today, the Peninsula remains roughly fifty percent undeveloped and protected habitat affirming that like Kenny McLean, David Head and Honours Golf before them, Thistle Hill Properties is making sure George C. Meyers’ original vision for his foundation lands is being responsibly maintained. Comparable to the prehistoric cultures who first inhabited this area and the settlers who arrived in the early 1800s, they understand the importance of caring for our natural surroundings. With the recent renovations focusing on the golf course, clubhouse and the improvement of the overall agronomic conditions of the property, it’s apparent that Thistle Hill Properties is committed to the idea that golf is more than a game. The Peninsula remains to be one of the premier golf communities of the southeast and a shining example of their belief that the pastime builds character, inspires important principals and ultimately brings people together.